As the 2000s came to a close and live music audiences were increasingly illuminated by scores of LCD screens snapping photos or video clips, a plea arose from many musicians, fans, and venue owners alike: enjoy the show, but do so with your cameras in your pockets. In late 2009, Apple, whose iPhones were the primary tool for concert photography, took the opportunity to answer this request through technological means. The company applied for a patent that could remotely control their own cameras through infrared beams, which, as shown in an illustration, could disable smartphone cameras for those musicians who didn't want to be photographed. This past June 28, the Patently Apple blog reported that the patent (first published in 2011) had been approved.

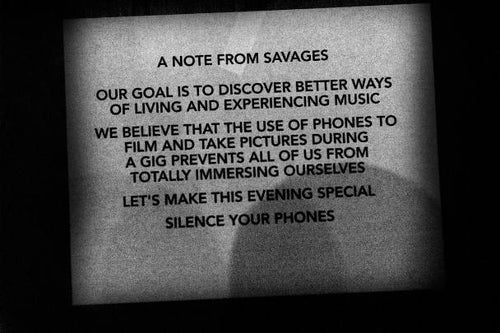

In the six years since Apple's application, iPhones have become the most popular device for amateur photography, and the pleas to attendees have multiplied as well. Most concert venues allow artists and their management to set the terms for amateur photography, and many musicians have turned to a variety of rhetorical means to rein in the practice. Savages posted a sign at gigs telling audience members that recording the gigs prevents everyone from "totally immersing themselves," while The Yeah Yeah Yeahs simply told fans to "put that shit away." She & Him asked one audience to put down the cameras and watch the show "in 3D," while Don Henley issued an appeal to future attendees of Eagles reunion concerts: "We'd like for them to experience it for the first time in the audience rather than...on a crappy video that sounds horrible." Prince, ever the control-freak, actually used his own security detail to enforce his no-camera wishes. Reclusive singer-songwriter Jeff Mangum banned photography at his concerts, one critic assumed, to protect his enigmatic allure. It's not just the musicians, either—many of their fans see such requests as a righteous attempt to re-assert control of a performance over unregulated technology.

Yet, also during those same six years, smartphone cameras have evolved not merely into archival tools for everyday experience, but in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and the Orlando nightclub massacre, they are now understood as means for emergency communication and possible legal documentation. Being without a smartphone camera at a concert could make many people feel much less safe. Apple's own dealings with federal law enforcement over issues of privacy and national security also impact the ideas contained within this patent. In the wake of the December 2015 San Bernardino massacre, Apple refused to comply with an FBI order to create a security "backdoor" to one shooter's iPhone, arguing that, should it leak into the wrong hands, such software could compromise every iPhone user's private data.

Though disabling a camera at a concert is obviously many worlds apart from accessing data on a terrorist's phone, the thought of Apple providing the ability to remotely deactivate a device emerges in a vastly different techno-political landscape in 2016 than 2009. Think about the San Bernardino issue in reverse: what if police departments were able to use the same technology during otherwise peaceful political protests? The image of an "on-off" toggle in the patent document demonstrates that, even if implemented, the infrared feature might be more of an opt-in, more relevant to delivering information for museum exhibit photographers than automatically disabling cameras. It's also entirely possible that Apple's application was filed, like many others, simply to ensure that subsequent others wouldn't trespass on this specific idea.

But what about...a bag with a lock on it? In 2014, the San Francisco startup Yondr emerged with a (not uncontroversial) Stone Age version of Apple's infrared patent: a locked phone pouch that can only be opened by scanning it in the lobby or outer concourse of the venue. Yondr has been adopted primarily by stand-up comedians to keep early drafts of material off YouTube, but Alicia Keys and the Lumineers have embraced it as a way not only to eliminate the circulation of material, but to create a wholly "phone-free" space to enjoy a performance.

Apple, which built its reputation on sleek objects that reduce cultural clutter, would never release something so humble as a lockable bag. An infrared beam does the same work invisibly, and with more specificity. But the primary logic driving both innovations is much the same, and reaches beyond concerts to everyday experience: removing technology leads to a deeper, richer live music experience. Of course, this means ignoring the technologies that make such events possible: even the most intimate club shows are heavily mediated, from lighting to mic placement, guitar pedals, computerized loops, amplification and speakers. There's no real or pure space outside of technology at pop and rock concerts. There are only ways of arguing aboutwhich technologies are or aren't appropriate.

Instead of adopting Apple's infrared solution, a much better remedy is to simply let these discussions continue. Let musicians and audiences work through the process as a dialogue, don't cauterize them by flipping a switch. The record business learned from the failure of Digital Rights Management—which used an imperceptible technology to limit the actions of paying mp3 consumers—that digital recordings need to move freely to reach their cultural and social potential. The same applies to the concert business: by transforming a live event into a visual record, concert snapshots are an oft-irritating way to capture a fleeting moment, but they're also a essential keepsake and form of social currency for millions of paying fans. So yes, keep posting signs in venues and making declarations from the stage, and let people choose how to respond to them. Don't transform a flexible, productive social code into a rigid technological program.